Grandpa Lissajous — A Loop-de-Loop

"Back in my day, we deployed code by hand and hoped for the best. Now I sit in my chair and watch thirteen AI agents argue about it." — 👴 Grandpa Simpson, System Observer

Here's what my workflow actually looks like right now: nine iTerm tabs open, each running Kiro CLI with a different hat. I /paste an annotated screenshot of things I want fixed into one terminal and ask it to add bug fixes to the queue. Another tab is deploying and monitoring the deployment. A third is the core coding and implementation tab. A fourth switches to my Debug agent configuration so it can drive the browser. I'll have three or four projects running like this simultaneously, all day.

It's manual, but it's extremely fast. The problem is that it's me — I'm the orchestrator, the context holder, the one deciding which hat goes next. When I step away, everything stops.

So I'm running an experiment: codifying this manual-but-rapid process into automated Ralph Wiggum Loops. The concept of agent orchestration loops isn't new — but this particular experiment is. I chose to stick with a Simpsons theme to honour the current trend of calling them Ralph Wiggum loops, and because giving each agent a character personality turns out to genuinely change how they approach problems.

The Grandpa Loop is a 13-hat, event-driven AI orchestration architecture built on Ralph. Raw ideas enter one end; tested, reviewed, deployed, and committed code exits the other. Every hat is an AI agent with a single job, a defined contract, and absolutely no trust in the hat before it.

Named for the hat that watches over everything: Grandpa, the System Observer. He tunes the loop based on evidence. He's seen it all. He remembers everything — which is more than you can say for the original Grandpa, but that's what a scratchpad and an observer report are for. He complains constantly. And he's the reason the loop gets better over time.

Why "Loop"?

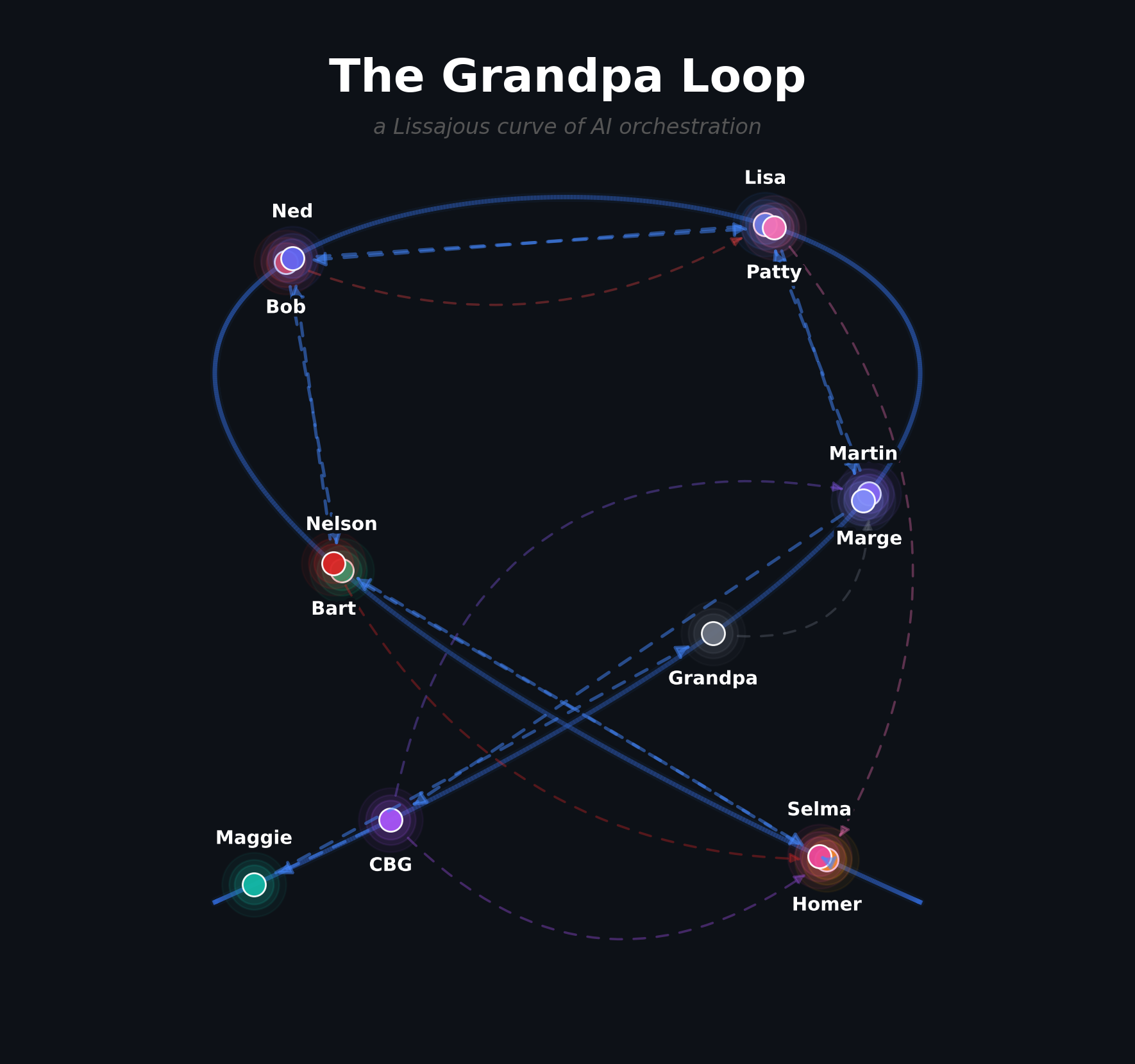

Calling it a "loop" is generous. A loop implies a clean circle — A to B to C and back to A. The Grandpa Loop is more like a Lissajous curve: a path that keeps crossing over itself, re-entering at unexpected points, tracing a shape that looks chaotic until you see the underlying pattern.

When Maggie commits, Grandpa observes, and the flow circles back to Marge for the next task — that's the main orbit. But when Bart breaks Homer's build, it cuts back across the middle. When Bob rejects Lisa's spec, it doubles back on itself. When Comic Book Guy finds a UX disaster, it arcs all the way from the end to the beginning. When Patty rejects the visuals, it crosses the build-fix loop at a different angle. The docs track runs parallel, untouched by any of it.

The result isn't a circle. It's an odd, twisted figure that traces the same space from different directions depending on what went wrong and where. The only exit is queue.empty — and even then, Grandpa gets the last word.

Most CI/CD pipelines are linear: build → test → deploy → done. The Grandpa Loop is self-correcting and self-intersecting. Bad specs get rejected before code is written. Bad code gets caught before it ships. Bad UX gets filed as new work. The curve keeps tracing, and the product gets better each pass.

The Interaction Graph

The Lissajous shape isn't decorative — it's what the flow actually looks like. The main orbit traces from Marge through to Grandpa, but the feedback arcs from Bart, Patty, and Comic Book Guy all cut back across to Homer, crossing the curve at different angles. The CBG-to-Marge triage arc sweeps from one end to the other. Grandpa's loop-back to Marge closes the figure.

Notice how Homer is the most connected node. Everything flows through the builder — specs arrive, failures return, visual rejections bounce back. Homer is the pressure point. When the loop is slow, it's usually Homer. When the loop is stuck, it's definitely Homer. Grandpa watches this closely.

The Cast

Thirteen hats, each named for the Simpsons character whose personality fits the job.

It starts with Marge, who curates the requirements queue — turning raw ideas and feedback into clean, prioritised task files. She hands each task to Lisa, the spec writer, who produces a detailed technical specification with interfaces, edge cases, and acceptance criteria defined.

Before any code gets written, Sideshow Bob reviews the spec. His job is adversarial: find the gaps, the ambiguities, the unstated assumptions. If the spec isn't airtight, it goes back to Lisa. Only specs that survive Bob's scrutiny move forward.

Nelson scouts the codebase next — mapping the relevant files, dependencies, and patterns that the builder will need. He produces a codebase report so the builder doesn't waste time exploring.

Then Homer builds. He's the pressure point of the entire system. Specs arrive from Lisa, failures return from Bart, visual rejections bounce back from Patty. Everything flows through the builder.

Once Homer finishes, the flow splits into two parallel tracks. On the test track, Selma deploys to staging, Bart tries to break it with targeted tests, Patty reviews the pixels for design compliance and responsiveness, and Comic Book Guy walks through real user journeys against the live staging environment. On the docs track, Ned updates the documentation and Martin commits it — independently, without waiting for tests to pass.

At the end, Maggie commits the code. She's the quiet one — she just gets it done.

And watching over all of it sits Grandpa, the System Observer. He tracks iteration counts, failure patterns, and cycle times. He tunes the loop configuration based on evidence. He complains constantly. And he's the reason the loop gets better over time.

The Five Feedback Loops

The Grandpa Loop isn't a straight pipeline — it's a system of interlocking feedback loops. This is what makes it self-correcting, and what separates it from a dumb CI/CD chain.

Spec Revision

A spec that reaches the builder with ambiguities or gaps will cost hours to untangle. The cheaper option is to catch it early — have someone adversarial read the spec before any code is written, and send it back if it's not airtight. The goal is to ensure that by the time the builder sees a spec, every interface is defined, every edge case has a strategy, and there's nothing left to interpret. The spec goes back and forth until the critic can't find holes. A rejected spec costs minutes. A bad spec that survives costs the entire build-test-deploy cycle. So we named the critic after the character who takes genuine pleasure in finding flaws and sending people back to try again — and that's why he's Sideshow Bob.

Build Fix

The most common loop in the system. Code gets built, deployed to staging, and then someone tries to break it. When they succeed — and they usually do — the failure goes back to the builder with specific reproduction steps. The builder fixes, staging redeploys, and the tester tries again. This can cycle many times, and that's by design. Each cycle narrows the gap between what was built and what actually works. The tester's job isn't to confirm the build works — it's to prove it doesn't. We needed someone whose entire personality is finding ways to cause trouble, someone who genuinely enjoys watching things break. Naturally, we called him Bart.

Visual Fix

Automated tests can tell you whether a function returns the right value. They can't tell you whether the button looks wrong, the layout collapsed at 375px, or the spacing feels off. Visual review catches the things that users notice first and engineers notice last. When the visuals don't meet the bar — design system compliance, responsive breakpoints, accessibility — the rejection goes back to the builder and the entire test pipeline reruns from staging. It's expensive, which is why it comes after the functional tests. No point reviewing pixels on a page that doesn't work yet. The reviewer needed to be someone with impossibly high standards and zero patience for excuses, which is exactly why we went with Patty.

UX Fix

This is the most expensive feedback loop, and intentionally the last gate before a commit. Everything else has passed — the code compiles, the tests pass, the visuals look right. But does the product actually work the way a real person would use it? Someone walks through actual user journeys against the live staging environment: log in, configure something, try the main workflow, see what happens when things go wrong. If a user can't complete a journey, the commit is blocked and the whole pipeline reruns. It's costly, which is why every cheaper check runs first. The inspector needed to be someone who takes the user experience personally, someone who would rather block a release than let a bad flow ship. We gave the job to the one character who has never let a subpar experience go unremarked — Comic Book Guy.

UX Triage

Not every issue found during UX inspection is a blocker. Some are rough edges, confusing labels, minor dead ends — things that don't prevent the user from completing their journey but make the experience worse. These get written up as new tasks and fed back into the requirements queue for the next iteration. The loop feeds itself: discovery creates work, work gets built, the build gets inspected, inspection creates more discovery. This is how the backlog stays honest — it's not just what the team thinks needs doing, it's what actual usage reveals. The person who organises this chaos into clean, prioritised task files with testable acceptance criteria is the same person who keeps the household running despite everyone else's best efforts to create disorder. That's why she's Marge.

The Parallel Track

After Homer finishes building, two things happen simultaneously.

The test track flows through Selma, Bart, Patty, Comic Book Guy, and finally Maggie — deploying, testing, reviewing, and committing the code.

The docs track flows through Ned and Martin — updating documentation and committing it independently.

Docs don't wait for tests. Tests don't wait for docs. They converge at the end with two independent commits from one build event. This is intentional. Ned shouldn't be blocked because Bart found a bug. Martin shouldn't wait for Patty to approve pixels. Parallelism where the dependencies allow it.

Why Not Just PDD?

Prompt-Driven Development gives you a planner and a builder. That's a good start. But it's like having an architect and a bricklayer and calling it a construction company. Where's the inspector? The tester? The person who checks whether the door actually opens?

The Grandpa Loop adds three things that standard PDD patterns don't have: an observer who tunes the system itself, a manual tester reborn as AI, and a set of interlocking feedback loops that make the pipeline self-correcting rather than self-congratulating.

Grandpa: The Observer Who Fixes the Machine

Grandpa's approach to system tuning.

Most orchestration systems have a fixed configuration. You set it up, you run it, and when it breaks you go in and fix it yourself. Grandpa changes that.

Grandpa sits in his armchair and watches. He watches Homer and Bart cycle back and forth three times on the same bug. He watches Lisa's specs get rejected twice in a row. He watches iterations climb without commits. He watches, and he waits, and he takes notes in his observer report.

And then — only then — he reaches for the mallet.

Grandpa's tuning follows the scientific method, which is a fancy way of saying he doesn't panic. He observes a pattern across at least two iterations. He writes down what he thinks is wrong. He waits to see if it happens again. Then he makes one minimal change to the loop configuration — maybe increasing Homer's max activations, maybe tightening a guardrail, maybe adjusting the memory budget — and he watches to see if it helps.

This is the opposite of how most people manage AI pipelines. The usual approach is to notice something's wrong, immediately change five things, and then wonder why it's still broken (or broken in a new way). Grandpa changes one thing at a time and documents every change with rationale. He's not fast. He's not flashy. But the loop gets measurably better over time because someone is actually watching it and making evidence-based adjustments.

The key insight is that the orchestration system itself is a thing that needs maintenance. Not just the code it produces — the pipeline that produces the code. Grandpa is the hat that maintains the machine, not the product. He's meta. He's the loop watching the loop.

And yes, sometimes the fix is just hitting it with a mallet. But it's a carefully considered mallet strike, after extensive observation from the armchair.

Comic Book Guy: The Return of the Manual Tester

The software industry spent twenty years trying to eliminate manual testing. We automated everything. Unit tests, integration tests, E2E tests, contract tests, property tests, mutation tests, visual regression tests. We built elaborate CI pipelines that run thousands of checks on every commit.

And yet. Users still find bugs that no automated test catches. They click things in the wrong order. They paste emoji into number fields. They resize the browser to 400px wide and wonder why the layout exploded. They try to use the product the way a human actually uses a product, which turns out to be nothing like the way a developer writes a test.

Manual testing was never the problem. Manual testing was expensive, slow, inconsistent, and didn't scale. But the thing it tested — real user journeys, end-to-end, with all the messy human behavior — was always valuable. We threw out the baby with the bathwater.

Comic Book Guy brings it back.

He maintains a library of user journey scripts — not automated test scripts, but narrative descriptions of what a real user would try to do. "Log in, connect an AWS account, create a coding agent, ask it to build something." He loads up the staging environment in a real browser, walks through each script step by step, and records what happens. Did the button work? Did the page load? Did the error message make sense? Could a new user figure out what to do next?

When something doesn't work, he doesn't just file a bug. He writes a scathing review — reproduction steps, expected vs actual behavior, screenshots, and a priority assessment. Worst. UX. Ever. These get written as task files that Marge picks up in the next iteration. Discovery feeds the backlog.

The scripts persist across iterations and grow over time. Every time Comic Book Guy explores a new user journey, he adds a script for it. The test coverage of real user behavior expands with every loop. And unlike a human manual tester, Comic Book Guy doesn't get bored, doesn't skip steps, and doesn't forget to test the thing that broke last time.

He's also the only hat that can block a commit based on vibes. If the automated tests all pass but the UX feels wrong — confusing flow, missing affordance, dead-end state — Comic Book Guy can emit ux.blocked and send it back to Homer. No other hat has that power. Bart can only fail on evidence. Patty can only fail on visual criteria. Comic Book Guy can fail on "a real user would be confused here," and that's by design.

This is the hat that catches the bugs your test suite never will, because your test suite tests what you thought of, and Comic Book Guy tests what a user would actually do.

Backpressure: The Law of the Loop

If you can't prove it, it didn't happen.

This is the single most important design principle. No hat can declare success without evidence. Not "I think it works." Not "it should be fine." Proof.

Homer must pass every quality gate — tests, compilation, linting, formatting, secrets scanning — before he's allowed to say he's done. Bart must provide structured evidence covering E2E tests, adversarial scenarios, accessibility, and YAGNI compliance. Patty must confirm responsiveness, accessibility, and design system alignment.

The evidence format is validated by the CLI. Vague prose gets rejected. This isn't bureaucracy — it's the mechanism that prevents the loop from lying to itself.

Guardrails

Every hat in the loop operates under a shared set of guardrails — non-negotiable rules that keep the system honest. Without them, thirteen autonomous agents would drift, over-engineer, or quietly ignore each other's contracts.

The guardrails enforce discipline at the boundaries. Each hat starts every iteration with fresh context rather than relying on stale memory. Backpressure is mandatory: no hat can declare "done" without evidence that the work actually meets its contract. Scope is enforced — a hat that starts modifying files outside its current task gets flagged.

Some guardrails are about engineering taste. YAGNI and KISS aren't suggestions — they're rules. Speculative features, premature abstractions, and "while I'm here" changes get rejected. Others are about decision-making under uncertainty: every hat scores its confidence on key decisions, and anything below a threshold defaults to the safe option with the uncertainty documented.

Grandpa watches all of this. When guardrails get violated, he notices — and the loop configuration gets tighter next iteration.

The Derivative Loops

The Grandpa Loop is the full 13-hat pipeline. Sometimes you don't need all thirteen arguing at once. For focused work, we extract subsets that inherit the same guardrails, backpressure rules, and Simpsons personality — just with fewer hats and a tighter budget.

The Bugfix Loop sends Nelson to reproduce the bug with a failing test, Homer to write the minimal fix, Bart to try to break it, and Maggie to commit. Four hats. Scientific method: observe, hypothesize, test, fix. If Bart's verification fails, it cycles back to Nelson with context about why the fix didn't work.

The Deploy Loop sends Selma to build and deploy, then Bart to verify the deployment is healthy. Takes a target — staging, production, or both. When deploying both, staging must succeed before production starts. Bart checks health endpoints, validates config, and runs visual smoke tests against each environment.

The UX Discovery Loop sends Comic Book Guy on a full exploratory sweep of staging, then Marge triages everything he finds into the task backlog. Pure discovery — no fixes, no code changes. Run this when you want to know what's broken before deciding what to fix.

| Loop | Hats | When to Use |

|---|---|---|

| Grandpa Loop | All 13 | Full feature development — idea to shipped code |

| Bugfix Loop | Nelson → Homer → Bart → Maggie | Known bug. Reproduce, fix, verify, commit. |

| Deploy Loop | Selma → Bart | Ship what's already built to staging, prod, or both. |

| UX Discovery | Comic Book Guy → Marge | Find issues. Triage into backlog. No fixes. |

To run any derivative, point Ralph at its config file. The full Grandpa Loop reads the prompt file for work and runs until the queue is empty. The derivatives can take an inline prompt describing the specific bug to fix or environment to deploy — or they'll read the prompt file like the main loop does.

"I used to be with it. Then they changed what 'it' was. Now what I'm with isn't 'it', and what's 'it' seems weird and scary to me. But I still tune the loop." — 👴 Grandpa

So, Does It Work?

Honestly? Sometimes brilliantly. Sometimes not.

When the loop is firing well, it's genuinely impressive. A raw idea enters Marge's queue and emerges the other end as tested, reviewed, documented, deployed code — without a human touching it. The feedback loops catch real bugs. Bob finds real spec gaps. Patty catches real visual regressions. The system self-corrects in ways that a linear pipeline never could.

But it's an experiment, and experiments have failure modes.

Time is the real currency. The API costs are negligible compared to an engineer's time — a full Grandpa Loop run costs less than a coffee. The question isn't whether you can afford to run it, it's whether you can afford not to. Manually driving each PDD step yourself means copy-pasting context between prompts, remembering where you left off, and losing your train of thought every time you switch tasks. The loop does all of that automatically, and unlike you, it doesn't get tired at 11pm and ship a bug because it wanted to be done.

The loop can be slow. Thirteen hats means thirteen LLM calls per iteration, minimum — more when feedback loops trigger. For a quick bug fix, the Bugfix Loop is the right tool. Running the full Grandpa Loop for a one-line change is like hiring an orchestra to play a doorbell.

What the experiment has convinced me of is that the orchestration pattern itself is sound. Separating concerns into single-responsibility agents with adversarial feedback loops produces better output than a single agent trying to do everything. The Simpsons framing isn't just whimsy — giving each agent a distinct personality and set of constraints genuinely changes how they approach problems.

Whether it's practical for production use today depends on your tolerance for cost, latency, and the occasional commit that makes you sigh. But as models get faster, cheaper, and better at maintaining context — and they will — the economics shift. The architecture is ready. The models just need to catch up.

In the meantime, there's something deeply satisfying about kicking off the Grandpa Loop before bed and waking up to a pull request from thirteen Simpsons characters who spent the night arguing about your code. Homer built it. Bart broke it. Patty rejected the pixels twice. And Grandpa left a note saying the loop is running 12% faster than last week.

I sleep. They ship. That's the dream.

If this resonates — if you're already running your own version of this with multiple terminals and a mental model of which hat goes next — I'd love to hear about it. Try it. Break it. Build your own derivative loops. And let me know how you go — message me on LinkedIn.

"The loop doesn't need to be perfect. It just needs to be better than doing it all yourself at 2am." — 👴 Grandpa, after his third observer report of the evening